Introduction I have never taken gender for granted. As a very young girl, I was convinced that I'd grow up to be a big, strong man; needless to say I was somewhat disappointed when puberty hit and made it quite clear that was not going to happen. As a short-haired, overweight tomboy, I grew used to adults calling me "son" and, "young man," and as a masculine woman have come to expect the occasional "sir." But I am not transgendered; I've grown to love being a woman, to appreciate my female body, and to value my identity as a lesbian. I do not feel"like a man" and do not want to be one; still, I am often accused of harboring such a desire. I am told that I dress like a man, I talk like a man, and I look like a man; surely I must want to be a man? I credit Judith Halberstam and her book Female Masculinity with finally providing me with a rebuttal: I am not like a man; I am simply a masculine woman. Masculinity, Halberstam clarifies, is not equivalent to maleness; it is a set of specific behaviors and attitudes that are available to all who would access them, including women. In semeiosic terms, then, masculinity is a set of signs that are assumed by most to be indexical to gender, which they are not. C. S. Peirce explained that an indexical sign is one which bears a real and physical relationship to the thing it represents; a fever is therefore an index of infection, just as facial hair is an index of testosterone -- although not necessarily of maleness. Masculinity, however, is more properly symbolic; the relationship it bears to the thing it represents is maintained strictly by social convention, and not through any actual physical relationship. As a masculine woman, I have broken with convention and adopted a personal style which is, in some ways, incorrectly indexed to maleness. But with the semeiosic bonds of indexicality and social convention collapsed, the signs of masculinity are revealed for the gender ambivalent behaviors and attitudes that they are. Masculinity, being in essence gender-free, takes many forms apart from maleness; maleness, however, carries a specific social demand for its emphatic expression. Males must in fact perform masculinity in an almost hyperbolic fashion in order to be convincing as men, while females must deny it all but the smallest expression; the same can be said, in reverse, of femininity. Such are the performative demands of gender in the work-a-day world, where most of us struggle to be naturalized. Importantly, this Butlerian gender performativity is not perceived as performance, by either the actor or the spectator; it is largely unconscious and fully internalized. But when gendered signs are consciously hyperbolized and presented expressly as performance, we arrive, I suggest, at gender theatricality. Gender theatricality is more commonly known as drag. While generally conceptualized as cross-dressed behavior, drag can also be presented as self-same hyperbolized gender: witness the Village People. Drag, by nature gender-disruptive, is an intrinsically"queer" form of expression, linked specifically by various theorists to gay male culture. It was while watching Jennie Livingston's Paris is Burning, however, that I found myself questioning the gender balance of drag; surely there were some women doing it? Strikingly ethnographic, Livingston's drag queen documentary was yet another book in the rapidly growing library on feminine drag. But while drag queens from Ru Paul to Priscilla, Queen of the Desert have found parallel acceptance in both popular media and the academy, masculine drag remains a question largely un-asked. I was not sure, at the outset of this project, whether or not there even was any such thing as a drag king, let alone in New York. Still, the idea was intriguing. What might a drag king be like? Not the mirror image of a queen, I imagined, for women are not merely the mirror of men. What might constitute masculine drag? Why might women do it? What meanings might it carry? The temptation to begin by comparing kings to queens was great, but one I determined to avoid. Enough has been spoken of men, I reasoned; women exist on their own without necessary reference to them. I decided to approach my inquiry empirically in the form of ethnographic fieldwork, seeking out scenes and informants, dealing only with what I could see and hear for myself. Utilizing various texts to gain an historical sense of masculine drag, I went out into the clubs and simply introduced myself to the kings that I found. I attended dozens of shows at different venues, socialized with some of the performers, and did one-on-one on-camera interviews. I had no idea what I might find, but I was specifically hoping for one thing: community. Every ethnography I had ever read was based on a community of individuals living or working together in a particular place; the genre seemed to demand it. While New York City is a pretty big place, I hoped at least to find a group of people committed to a common goal, a similar aesthetic, a particular political message, or minimally, a sort of camaraderie. Apparently, I missed out on most of these things by a matter of months; what I found instead were relatively isolated individuals, each with their own methodology. Yet, despite the incredible diversity of styles, opinions, goals and identities, commonalities emerged -- only not where I expected them to. In this manner the work has been truly enlightening, and I feel that I have grown, both intellectually and emotionally, as a result.

In April of 1998 I began attending a series of Thursday night drag shows at a lesbian bar called Crazy Nanny's in the western part of New York City's Greenwich Village. A two-story establishment, the lower level houses a bar and a pool table; upstairs lies a second bar, a small seating area, and a medium-sized dance floor with a small area set aside for a stage. Home to a weekly event called Dragnet, Crazy Nanny's provided a forum for both drag kings and queens, with attempted emphasis on the kings. The shows, hosted by a lesbian comic, usually began after midnight and featured anywhere from one to four drag performers. The great majority of acts I saw at Crazy Nanny's were lip-synched, and most were by women of color. Drag kings Dréd, Shane, Antonio Caputo and Macha made regular appearances there, while other drag artists occasioned the bar socially. Playing mostly hip-hop, R&B, and dance music, Crazy Nanny's attracted a primarily black and Latina group of women in their twenties and thirties. I attended weekly performances with some regularity for a period of approximately eight months, at which time I curtailed my fieldwork activities. Drag king Murray Hill performed in a variety of venues, most of which were straight nightclubs; the first time I saw him perform was at a lounge called Life, whose logo was a stylized depiction of a sperm penetrating an ovum. The club was chic and pricey, providing only a drink menu with prices as high as $300.00. Playing techno-industrial and alternative dance music, it attracted a young, white, straight clientele; I sat for several hours and watched kids in their twenties nurse the single drink they could afford to buy. I also saw Murray when he appeared with drag king Mo B. Dick and his female sidekick, Bob, at Fez, a performance space located under the Time Cafe on Lafayette Street. There, the crowd was mixed and a little bit older, but still predominantly straight and white. Serving mid-sized meals and desserts, Fez came closest to providing a genuine cabaret atmosphere. Long tables were lined up at angles facing the stage, and several booths lined the walls. Drag kings Mo B. Dick, Murray Hill, Dréd, Antonio Caputo, and Macha, as well as Shelly Mars, all appeared at various times at Meow Mix, a lesbian bar on Houston Street in the East Village. Playing mostly alternative rock, this club also attracted predominantly white women. They were, however, decidedly young and, "alternative"; Meow Mix provided the most tattoos and piercings per square foot. The basement, cramped and sparse, was the setting for a Dyke TV benefit featuring Antonio Caputo, Macha, and Shelly Mars; the stage for this event was barely two square feet, and the kings were forced to negotiate a small piece of the floor upon which the women were seated. The more roomy ground floor was where Judith Halberstam celebrated the release of her book, Female Masculinity, by inviting the kings to perform upon a medium-sized, slightly elevated platform. Diane Torr and Shelly Mars appeared together at a West Village nightclub called Mother for an AIDS fundraising event that Torr had organized. Staffed mostly by drag queens, Mother was decidedly queer, white and thirty-something; men outnumbered the women by more than two to one. By contrast, the Club Casanova show (featuring Mo B. Dick, Bob, Dréd, Antonio Caputo, and Lucky 7) at Axis in Chelsea attracted an exclusively lesbian crowd; they, too, were white and predominantly thirty-something. While the stage at Mother was barely two feet from curtain to edge, Axis utilized a rather large, elevated seating area as a performance space; both spaces functioned to place the performers above the crowd and almost out of reach. Other performance venues included outdoor festivals and Gay Pride events, a student-organized Diva Ball at New York University, and a cavernous space called The Brooklyn Anchorage located inside the stone foundation of the Brooklyn Bridge.

A considerable amount of information, especially with regard to recent history, was gleaned from viewing videotapes; significant here were the contributions of Lucia Davis, an independent filmmaker who has been documenting the drag kings of New York since 1995. Her films, Kings of New York (1996), Murray for Mayor (1997), and Men We Love (1997), as well as her insights, were instrumental in providing background on the more cohesive drag king scene that existed seemingly just before my project began. They allowed me also to witness the infancy and recognize the maturation of kings such as Mo B. Dick, Murray Hill, Dréd and Shane (previously known as Shon). Monika Treut's Virgin Machine (1988) provided me with an opportunity to see Shelly Mars doing masculine drag long before most of the other kings began performing; her scene as Martin steals the film. Diane Torr was kind enough to provide me with privately-made videotapes of several performances, as well as a copy of HBO's Girls Will Be Boys (1994), documenting her Drag King for a Day workshop. I, myself, shot several hours of videotaped performances for the purposes of repeated viewing and eventual analysis; I was assisted in this by Justine Frankovich, a friend and graduate film student.

Since the first drag king contests of the early 1990s, literally hundreds of women have performed masculine drag in New York City; some constructed minor careers for themselves, building name recognition within at least the lesbian community. The great majority, however, appear to have participated on a limited basis for a limited time, and even a lot of the"stars" eventually walked away. In the course of my fieldwork I discovered approximately twelve women currently entertaining as drag kings in New York City, most of whom had been doing so for more than two years. There were numerous other women who had, in the past, performed drag, but since I could not see their performances for myself, I decided that it would be unwise to attempt to include them in my analysis. I therefore confined my interviews to those whose performances I could personally witness. While I interviewed only nine women in depth and on-camera, I chatted informally with up to a dozen more who were, or had formerly been, involved in performing masculine drag. On-camera interviews took place either in the home of the informant, or outdoors in a public space such as a park; I did one interview on a black tar rooftop in ninety-five degree heat, and another on a Sixth Avenue sidewalk in the din of rush-hour traffic. I interviewed each informant formally only once, at a pre-arranged time and location, after obtaining written consent to videotape. Interview lengths were constrained primarily by battery life and tape length; where at first I thought this a disadvantage, I later began to appreciate it for the structure it provided. I found that knowing I had only a limited amount of time encouraged me to keep the conversation focused, avoiding any interesting but nonproductive digressions. Interviews seemed to grow tiresome or repetitive after an hour to an hour and a half, about as long as two to three tapes or a single battery charge might last; indeed, most of my informants grew tired or annoyed if the interview threatened to go on any longer. I had many informal exchanges with numerous drag artists, as well as their friends, romantic partners, family members and fans. At Crazy Nanny's, I got to know the manager and the event promoter, as well as the staff and a lot of the regulars. Where in the beginning, I had entered the bar anxious and feeling out of place, by the end it had become a sort of"Cheers" to me -- a place where everybody knew my name. While I tried to maintain something of an air of seriousness and professionalism there, I enjoyed myself immensely and made several new friends.

•The Camcorder When I began planning out my fieldwork, one of the first issues I considered was the question of how to record my interviews. Afraid at first of souring the process by introducing an artificial element, I contemplated not recording them at all, but the burden of representation seemed too great without the words, themselves, to fall back on. I thought then of simply recording them on cassette tape, but the image of my own face, bored to tears over the necessary transcriptions, convinced me that videotape was a better choice. Having moved from one extreme to the other, I plunged forward into rationalization: Surely it is better to watch the face of someone speaking than simply to listen to her words; videotape would provide me with a wealth of information that audio tape could not. Simply setting up a formal interview had already introduced an element of artificiality to the exchange; why not go all the way? I could record on-stage performances as well as at home interviews, facilitating the anticipated comparison between person and persona. Besides, I reasoned, my informants are performers; they will want to be on camera. With this, I took my first naive steps into the realm of visual anthropology, where convenience battles constructedness and the researcher must find a way to strike a balance.

As the fieldworker leans out over the vessel, the skipper hails him with"Here's the fellow who's going to take photographs, boys." The observer is introduced as someone who has a job to do; he will be as active as they are. (Collier, 11) I am neither a filmmaker nor a photographer, but I learned through my research the power of the camera as a veritable all-access pass. The best example of this occurred during Gay Pride Weekend when I went to see drag kings Dréd and Shane perform on the main stage on Washington Street. It was a searingly hot day and the streets of the West Village were jam-packed with revelers. The police had literally fenced in pedestrians with barricades, funneling the throng through a narrow gauntlet of navy blue to selected points of access; my dreams of crossing Seventh Avenue South at Christopher Street were dashed as I was pushed along two blocks further south. It was nearly noon and I was already late in arriving, so I hurried west toward Washington Street and the staging area. The barricades were up, however, and I was led to a point about four blocks north of where I needed to be on Washington Street. Ahead of me, a sea of people, thousands upon thousands shuffling shoulder to shoulder through the ridiculously narrow passage of gutter that was the festival grounds; at the rate I was moving, I would miss Dréd, 's performance entirely. Exasperated and annoyed by the cattle-pen conditions, I made my way to the sidewalk and ducked behind the vendor trucks and stalls. Gingerly stepping over power cords and behind generators, I slipped through to the end of the block and exited Washington Street to walk down a parallel, uncrowded street. I came up on the main stage from behind but was disappointed to find the area blocked off and patrolled by security. Pressed for time, I stepped over the barrier and approached someone on staff for the event."I'm sorry," I smiled,"but I need to get through to the front of the stage. I'm here to shoot the show." Asked if I was on"the list," I replied,"I don't know, but you can ask drag king Dréd. He's expecting me." Hot and tired, the fellow simply looked at my camera bag and nodded."See him," he pointed, indicating a guard near the stage. Moments later I found myself immediately in front of the stage, at the head of a crowd of thousands. Feeling strangely empowered, I grinned and began setting up my gear. When I opened my tripod, several people stepped out of my way; when I began recording, they admonished each other not to block the camera. Folks offered their opinions as to the best angle to shoot from or the best performer to videotape, and I felt like a VIP. My camera battery died about halfway through the show but I stayed to watch anyway, letting them think I was still recording. I personally never shot any videotape at Crazy Nanny's, my primary venue, but Justine Frankovich came twice to do so on my behalf. I had already decided that I wanted everyone there to be comfortable with me as a regular, and I felt that a camera would only separate me from them. When Frankovich arrived with her gear I introduced her as"my camerawoman"; she claimed a perch which clearly obstructed the view of others, but no one complained. It was, in fact, the only time my presence at the club was noted on stage by the comic, who made a routine of"shouting out" the notables in the crowd. Childishly, I'd waited a while for that bit of recognition, and I was surprised that the camera inspired it. At places like Meow Mix and Mother my camera secured me a prime viewing position and a small degree of respect from the group assembled, who generally were concerned not to get in my way. Had I been without the camera, I likely would not have pushed my way to the front as I did, nor maintained such a steadfast position. The camera gave me courage in that regard, and an extra shot of confidence that I might be taken seriously as a professional. On one occasion it served, I think, to make me more interesting to a few women who paid a bit more attention to me than they otherwise might have. It certainly carried with it a sort of power, which I recognized immediately and did in fact attempt to manipulate. The camera did, however, have its drawbacks, and after several experiences I stopped bringing it with me to shows. It framed not only what I saw, but what I experienced. I found that operating the camcorder during a show forced me to focus on it, rather than the performance; it also tended to isolate me from the experience of the audience. With one eye closed and the other squinting into a viewfinder, I was truly half blind. On one occasion, my preoccupation with finding a suitable electric outlet once my battery had died essentially ruined my experience of the show. I missed nearly ten minutes in just seeking a spot; forced finally to shoot the action on stage from a distant DJ booth, I could neither see nor appreciate what was happening. Looking through the lens, I had a false sense of distance and entirely no idea of what was really going on around me. Hoping to produce a reasonably professional tape, I was concerned with lighting and exposure, framing, battery power, and tape length time. Sometimes poor lighting forced me to pull in closely on a drag king in order to make out his face; this meant that I did not see the full of his body during the act. Compelled to focus thusly on creating a product, I could little appreciate the creativity before me. It was only when I went home and viewed the tapes that I really enjoyed the performances, but I had retained no perspective at all on the reactions of the audience. Grateful now that I have them to watch, I wish only that somebody else had shot them. Sometimes the video camera had an impact on a particular performance. Its very presence appeared to demand the attention of the artist, but when faced with the promise of tips he could usually manage to ignore it. When a situation prevented the crowd from directly interacting with a performer, however, the camera could become an attractive audience. On several occasions I saw people play to it intentionally, unaware sometimes that I was not even recording. Under certain circumstances, I believe the videocamera actually enhanced a performance, its promise of repeated replayings providing added performance incentive; I have heard a few performers admit that this is the case. It was not difficult to obtain any performer's permission to film a show; what proved more complicated was explaining my purposes. This involved a kind of sales pitch which I recognized as such, but was anxious to render as genuine. Several of the women with whom I worked are seasoned performers who have grown somewhat used to having writers, photographers, and filmmakers around them; some were leery of being misrepresented or perhaps cheated out of whatever profit I might at some time earn through the use of my tapes. I assured them all that I had no intention of using my recordings for commercial purposes, explaining that if ever that were to happen, I would need to seek a separate, signed consent. I declared that I was not a filmmaker, but a student, intent on representing them to an academic community with the express purpose of earning my degree; I could not have been any more honest, and I am certain that it was appreciated. All of the women agreed to be filmed, but some were more concerned than others to elaborate their rights under our agreement. Eventually I arrived at a form I referred to as an"anti-release" because it allowed the signee to revoke my rights at virtually any time. (See Appendix.) Even this form raised some experienced eyebrows, to which I responded:"Change whatever you like and sign it, and I'll initial the changes." Most requested at least a screening before I showed any taped material; some asked only for private copies of what I had recorded.

Videotaping my interview sessions turned out to be rather complicated; artists expressed concerns ranging from privacy to dress, location and length. Some were reluctant to have me in their homes, while others offered me meals and return invitations. While all of the women signed my release form, in certain cases I had to expressly state that I would not be including this footage in my edited presentation reel; a performer anxious to be filmed in action is not always happy to expose her real self to the lens. Often it was evident that the content of our conversations was to be kept private and anonymous, and I promised nearly everyone that I would do so with regard to at least one matter. I resolved before beginning my research to videotape my interviews so as to have an audio-visual record to refer to when preparing my paper; it is a decision that had a notable impact on my results. Just the act of setting up a camera to face someone immediately creates not only an artificial environment, but an invisible audience and a heightened set of expectations. Roland Barthes told us,"Now, once I feel myself observed by the lens, everything changes: I constitute myself in the process of'posing,' I instantaneously make another body for myself, I transform myself in advance into an image" (10). Indeed, I often saw this very process occurring before my eyes as I pressed the"record, " button. Some of the women, professionally trained as actors, almost could not help but look into the lens when speaking to me, regardless of where I was seated. When I tried to anticipate this once by standing behind the tripod, my informant told me to"sit away from that so I don't have to stare at the camera. Jesus, that's what 60 Minutes does;" she then proceeded to look at it quite a bit, anyway. Another informant asked,"Do you want me to look at the camera?" "You can look at me," I responded;"you can look wherever you want to." She too, spoke more to it than to me. There was, for me, a constant conflict between the desire to make a good videotape and the need to do a good interview. While only a few informants posed and strutted specifically for the camera, I am certain that nearly every interview carried an edge of camera-influenced theatricality. On the other hand, as I said earlier, the camera did provide a sort of regular structure to the interviews, acting in some ways as an equalizer in terms of mood, setting, and length. It appeared to encourage verbosity in some and quietude in others, but I believe that most of my informants measured their words fairly carefully, knowing they were being recorded. Some felt a drive to be exceedingly productive and helpful, while others, upon later viewing, looked somewhat stricken by the process. While happy indeed to have these tapes to refer to, I find myself suddenly understanding the perspective of those who might wish for more covert recording methods. Unethical though it is, one yearns for that lost degree of naturalness which is eroded by the presence of a visible camera.

The Proper Use of Pronouns The reader may have noticed my use of the word, "he" when referring to the women involved in this project; I would here point out that this is in fact not the case. I learned from several of the drag kings that proper etiquette demands they be addressed as "he" when in drag; my usage of a masculine pronoun is intended to denote that I am speaking of a male character rather than the woman who portrays him. Maureen Fischer (a.k.a. Mo B. Dick) put it best:"If I'm working hard to keep this male persona, this illusion of being male, to refer to me as'she' just defaces everything I'm doing. It negates everything I'm doing. It tells me that I'm not passing. It's infuriating." Using the wrong pronoun is a mistake that many drag queen hostesses make at mixed king/queen events. Explaining that gay men tend to call everyone"girl," Fischer noted that lesbians rarely engage in such cross-gendered naming; even the most masculine of women almost never call each other"boy." When a drag queen refers to a king as"she," she (the queen) may be doing so out of a sense of inclusive camaraderie, rather than an overt denial of masculine success. Despite friendly intentions, several of the kings made it clear to me that this, in the context of a performance, is an inappropriate usage which indicates a refusal to recognize a crossing of gender with which drag queens, in particular, should be familiar."I would never deface a drag queen and say,'he'," Fischer told me."That's never done. Never." In the spirit of respect, then, I refer to all drag king personae as"he."

Fame and Pseudonymity Under ordinary circumstances an ethnographer uses pseudonyms to refer to her informants; using a videocamera renders that exercise fairly useless. More importantly, in this particular case, the informants are performers who seek employment and fame, and the camera offers much-needed exposure. Many of the women I worked with in fact expressed a desire to be recognized for their efforts, to have their contributions documented, and their performances shown to others. It was obvious to me from the beginning that they would want me to use their real names. Yet, some told me incredibly personal things. While it was clear that I had permission to use whatever information I was given in the formulation of my thesis, it was also obvious to me that a few desired anonymity on certain topics. Therefore I have taken an approach which detaches the more sensitive statements from those who made them, while attributing the more harmless ones correctly to their authors. Despite the sort of tabloid, gossip column effect this may produce, I believe it is the best compromise I can achieve under the circumstances.

People-Boxes It is unfortunately necessary to define a few terms before moving on. I say"unfortunately" because language works best when it is allowed some fluidity, yet critical discussion demands that we make certain we are all talking about the same thing. I did, in the course of my research, attempt to elicit some definitions from the performers themselves, but found, firstly, that no two were the same and secondly, that many grew annoyed when asked to define themselves. No one likes to be put into a box or placed into a file, and most don't appreciate having limits drawn around their set of possibilities. This was the case with regard to everything from sexual orientation to gender identity. It falls to me then, to define my own terms so that I may demonstrate internal consistency at least. "What is a drag king?" I asked this of nearly everyone, and only a few actually answered: I'd define"drag" as dressing as something that you're not used to. Like for you, I would say drag is getting long hair with make-up and fake long nails and a dress and heels, because that's not something you'll ever do, probably. To me, drag king is performance, and cross-dressing is a lifestyle kind of a thing -- somebody who's dressing as a man and passing every day. I think a drag king is like a drag queen; it's about performance. It's about being big and larger than life perhaps, or stereotypical, taking those stereotypes and playing on them. Drag's a lot of different things. It's a lot of things for different people. For me it's all about parody, and that's pretty much it. Parody, and then I use it as a vehicle to express my feminist goals. Some automatically associate being in drag with pasting on facial hair. It's really a sort of performance aura or intention. . . or, you have to be passing. The main element of drag, to me, is parody. It's comedy. According to Judith Halberstam, who has spent a considerable amount of time researching drag kings,"A drag king is a female (usually) who dresses up in recognizably male costume and performs theatrically in that costume" (1998:232). While I find the formulation useful, I suggest instead a more expansive definition which recognizes the fact that costume is but one of a set of signs adopted by masculine drag artists. A drag king, male or female, expressly performs maleness by hyperbolizing the signs of masculinity; conversely, a drag queen expressly performs femaleness by hyperbolizing the signs of femininity. Biological maleness carries with it the social demand for an emphatic use of masculine signs; drag takes this one step further by intentionally hyperbolizing and theatricizing those signs, regardless of gender. Such gender theatricality may sometimes attempt to render itself as genuine and seek to pass, but its origins always lay in a conscious performance of gendered stereotypes which are themselves hyperbolic. Passing women, by contrast, live their lives as men, preferring, as they do, understatement to hyperbole. Like biological men, they utilize the signs of masculinity emphatically; emphasis and hyperbole are quite different things. Gender theatricality, as defined earlier and above, is independent of sexual orientation; anyone can do it. Still, the fact remains that the great majority of drag artists are either gay, lesbian, or transgendered, and that all of the women with whom I worked built primary emotional and sexual relationships with other women. But when I asked them if there was any relationship between their sexual orientation and their work as drag artists, most responded negatively, attributing the choice instead to a profusion of feminist goals; only one suggested that it helped to have a sexual knowledge of women when entertaining as a drag king. Why then, were the drag kings all queer? In my introduction I suggested that since drag is by nature gender-disruptive, it has always come naturally to queers. But many scholars have linked drag to camp and seen both specifically as products of gay male culture; lesbians who did drag were simply borrowing the strategy (see Bergman; Meyer). I see this line of thinking as but another example of the pervasive tendency to view women as naught but a pale imitation of men. Drag, some claim, has a history among gay men that it simply does not among lesbians; therefore it must belong exclusively to gay male culture. I suggest rather that drag has something of a history among all gender transgressors, and that drag is attractive to all those who feel limited by their assigned gender roles. Women, however, had simply lost the space they had to perform it; the drag king concept, while"always available," never had the chance to develop"into a continuously generating tradition the way drag queen has." à While the first half of the 20th century saw a tradition of cross-dressing actresses, blues women and lounge singers flourish (see Halberstam; Faderman; Ferris), the feminist movement of the 1970s fostered the spread of an anti-male attitude among women, especially lesbians, who until rather recently had little desire to engage masculinity in any form. Masculine women were ridiculed within feminist ranks for imitating men, while lesbian couples with a butch-femme aesthetic were chastised for aping heterosexuality and perpetuating the patriarchy (see Nestle; Faderman; Rubin). There was simply no friendly space for a drag king. Several of the women I spoke to expressed surprise that they were, in fact, accepted among the more"P.C." lesbians, who"traditionally have hated men;" ¤ they did not expect their acts to go over as well as they did. It is true, I believe, that fifteen or twenty years ago, their acts would not have been well received. But audiences have changed. Drag kings have emerged in the'90s, I suggest, because the political environment has changed yet again, and men are no longer cast as villains. Post-feminists are less willing to see themselves as victims of a male enemy and more likely to consider themselves liberated and independent actors. Young women today refuse to acknowledge any sort of gender imbalance they cannot overcome, and many respect the"new man" as a vital contributor to society. The age of AIDS, too, has drawn lesbians and gay men together, where they have found certain shared aspects of culture and sexuality; a lesbian can accept her attraction to masculinity and still remain true to her politics. Women, feeling more secure in their gains and achievements, see themselves on a more equal footing with men. As men and masculinity grow in the esteem of women and lesbians, masculine women reap some of the benefits; because men are no longer perceived as threatening, it is safe once again for women to be masculine. It makes sense, then, that the post-feminist'90s have finally opened up a space for drag kings to exist; it also accounts for the fact that nearly all of my informants went for the feminist explanation of why they do drag. Since I will be using the term in this paper, it must be explained that a masculine woman who identifies as a lesbian is often referred to as"butch." According to Gayle Rubin,"Butch is most usefully understood as a category of lesbian gender that is constituted through the deployment and manipulation of masculine gender codes and symbols" (1992:467). Butch women are sometimes confused with drag kings because both are females who express masculinity. But unlike the drag king, a butch woman does not consider her masculinity to be an intentional performance, much less one that is specifically hyperbolized. It is who she is and not an act, and while some butch women do indeed pass as men, they do so without specific intent. Women who intentionally set out to pass as men generally recognize that they are performing maleness, rather than simply adopting certain signs associated with masculinity. Performing maleness requires not only the rejection of feminine signs but, as I have said, a certain emphatic expression of masculinity. It is a fine line to walk then, for a passing woman's performance of gender must not be excessively hyperbolized to the point that it reveals itself as an act; her life sometimes rests on the fact that the performance appears genuine. A female-to-male transgendered person, by contrast, genders himself as genuinely male; if he is"acting," is it only in the sense that the gender he performs has not been entirely internalized, and so must be consciously learned and habituated. Only the drag artist consciously acts out gender with some degree of hyperbolic theatricality, rather than simple internalized identification."Male impersonator," I suggest, is a catch-all term that may be applied to any woman self-identified as female who performs maleness, be it theatrically or in a temporary effort to pass."Genderfuck," however, is constituted by the conscious desire to escape from dichotomized gender; it is marked by the visible combination of both masculine and feminine signs, whether hyperbolic and theatricized, or naturalized in the form of androgyny or, in certain cases, butchness.

The following section is intended as a brief introduction to each of the women with whom I worked most closely. Since the reader can neither meet these performers nor view their performances, I have tried in these chapters to provide a general sense of how they presented themselves to me, both on the stage and off. The personal details provided here are done so by the express permission of the participants; where anonymity was desired, statements have been omitted and reserved for pseudonymous discussion elsewhere.

(photographer unknown) "Instead of being an angry woman, I became a funny man." - Maureen Fischer

The night I saw Paris is Burning, I hurried home to my computer. Logging on to Infoseek's search engine, I typed in"drag king" and hoped for a happy coincidence. Distressed at the return of only a short list of NASCAR websites, I switched to Yahoo and tried again; the very first site listed was that of New York's Club Casanova, the brainchild of Maureen Fischer, alias Mo B. Dick. A weekly event whose life expired shortly before I began my research, the Club lives on in the persons of its primary performers, foremost among them its creatrix, Mo Fisher. These are the people who formed my basic pool of informants, and most of the performances I saw were made by its constituent members. The Casanova website *, administered by a professional web designer, is extremely well put together, high-gloss, and information packed. It is also plainly politicized: The second page one accesses contains a running countdown, to the second, of the time left to go until the end of the current Mayoral administration. The first page details the events surrounding the birth and subsequent death of the Club: Mo B. Dick started Club Casanova with Mistress Formika in 1996 as the first weekly regular Drag King show in New York City. The idea was simply to give drag kings an outlet to express themselves, but what happened was an explosion. Queers, Hets, Bi's, Dykes, Bikes, Freaks, Punks, Monks, and everyone else came from miles around to see those sexy swaggering macho sex-machines strut their stuff. The proprietor of this madness, Mr. Mo B. Dick, put together some amazing shows for dazzled onlookers. Shows got more elaborate and exciting. But then the police came. New York's Mayor, Rudolph Giuliani -- referred to as"Ghouliani" by those less satisfied with his performance -- embarked in 1997 upon a much-publicized campaign to improve New Yorkers' "Quality of Life." While doing so, his litter squads targeted nearly everyone from butt-dropping smokers to coffee-drinking commuters. Specially singled out for legal attention, however, were the adult businesses. Utilizing oft-ignored legislation ("carryovers from Prohibition," the Casanova website informed me), the city set about closing as many peep shows and triple-x stores as possible, while archaic cabaret statutes forced several bars out of business. In 1998, one bar owner found a rather ironic way around the problem: He changed his policy to admit minors when accompanied by adults; thusly was his place no longer an"adult business." Eventually the tide turned against Cake, the East Village bar that had been a cozy home to Club Casanova every Sunday night. They were cited for two violations -- one for simply having curtains hung too low in their windows -- and a third would have meant the revocation of their liquor license, a loss the owners could ill afford. Backing away from the risk, they shut their doors. Fischer laments the loss of the venue as the beginning of the end of Club Casanova, speaking with disdain of the polished-wood sports bar that emerged in the space a few months later. The show moved to another venue but for Fisher, it was never the same. So Mr. Dick and the boys went on the road --"twenty-six shows in sixteen cities, folks, never been done before" -- and returned eventually to a dampened downtown scene. Feeling reasonably well-informed after this Club Casanova-sponsored education, I followed its advice and went the following Thursday night to Crazy Nanny's, a lesbian bar I'd virtually grown up in, where a new weekly drag event had been born. It was there, on the occasion of my third visit to Dragnet, that I met Mo Fischer. I'd been planning on calling her, but had been putting it off until I felt I understood my project a bit better; I wanted to have something intelligent to say to her, since it was clear to me that she was an intelligent person. Kate, who was promoting the event at the time, took the stage to introduce the show. She announced the presence of Mo B. Dick in the crowd, but when I turned around to look I saw no one in drag aside from the scheduled performers. There were a lot of butch women, to be sure, but none in drag. A short time later Kate pulled me by the arm and introduced me to perhaps the last person I'd expected to be Mo B. Dick. She was not in drag, of course, and I was somewhat shocked. For while the photos on the Casanova website had prepared me for the sharp and studly fellow pictured above, Mo Fischer turned out to be a beautiful, feminine, lipstick-wearing woman. I'd expected a drag king to be butch. Fischer has a head of short, thick, blond hair and big, blue eyes that always seem to be wide open; she looks at you with an intensity that seems to inquire constantly whether or not you are listening. Her facial structure is well-defined and somewhat square; she told me,"I've had female-to-male transsexuals say to me,'I love your jaw. I'd kill for that jaw.' They love my whole facial structure; they consider it more masculine." Slim and small-breasted, her body is well-suited to male drag but her presence is entirely feminine. Within moments of meeting her I was certain of her intelligence and passion for performance. Eager for intellectual engagement, immediately she began throwing information at me -- so much so that I embarassedly had to ask her to"save it for later," when I'd be able to record or take notes. She told me right off that to her, drag is very political, and then she began talking about gender inequality. Much as I wanted to have the conversation, Shane's act was starting and I could barely hear her over the music. I took her phone number and promised to call her the following week. I videotaped an interview with Fischer about a week later, fully two weeks before I actually saw her perform. I had seen several drag king performances at Crazy Nanny's by then, however, and read all of the Club Casanova press available on the web. Still, it is awkward to interview a performer one has never seen on stage, especially when it is the first interview one has ever conducted; fortunately, a silent mule could have done the job. Used to being interviewed, Fischer is very good at it and requires little assistance from the interviewer; consequently, she makes the perfect informant. When I arrived at her apartment she had books and videos waiting for me, as well as an extensive scrapbook of her own activities. She was helpful and informative, and quick to credit the work of others, both performers and academics. We discussed Esther Newton, Judith Butler, Kate Bornstein and Judith Halberstam, all of whom she was familiar with. I left her apartment that day with over two and one half hours of videotaped interview, every minute of it jam-packed with fundamental information, a stack of magazine and newspaper articles, and a list of books to read. My visit with Fischer had been more productive than my last trip to the library, and thanks to her, I was beginning to get an idea of what I was doing. I finally got to see her perform during Gay Pride Weekend at a special revival of the Club Casanova road show. They were booked into a large Chelsea night club called Axis, with an elevated stage that was inexplicably roped off. Fischer opened the show in the guise of the Reverend Jimmy Johnson, a southern preacher with a bad toupee who appeared to be on the spiritual equivalent of Ecstasy. He made his entrance into the crowd, shouting,"Hallelujah! Amen!" and sprinkling holy water on us as he passed. Taking the stage, he proclaimed loudly,"The Drag Kingdom is come!" and, reading from"The Book of More-Men," proceeded to address the crowd with Pentecostal fervor: "Brothers and Sisters, I want to read from the righteous book of the gender free. Right here in Chapter 13 it says, and I quote: and on the eighth day the gods realized that there must be a third sex. And then the gods created the royal family of the drag queens and the drag kings. Hallelujah!" Now here is a drag king, I thought, who's read Gilbert Herdt. Fully aware of the theory behind the performance, the Reverend condensed it for the audience: "Brothers and Sisters, many people ask me, they say, what is a drag king? What is it? What is it? What is this movement that's sweeping the nation? What is it? I'm here to tell you; I'm a special messenger. I am a Reverend. A drag king is a person who wants gender euphoria! A drag king is a person who has accepted their female masculinity! And a drag king is a person who likes fast cars and cheap women, Amen! Amen! Ooh, Lordy, I'm feelin' it!" Later on, Mo B. Dick made his first appearance on that roped-off stage. Virtually the first thing he did after introducing himself was to take that rope in his fist and ask us,"What the fuck is with the ropes? Right? They're ropin' us in!" He simply voiced what all of us were thinking."You know who's this? I'll tell you. I'll tell you, I asked tha' fella back there, god bless him, Scott, right? Giuliani! This shit is Giuliani! I'm not lyin'! Am I right? I said,'Get ridda tha' fuckin' ropes!' He says,'Buddy, I can't do that.' No joke. Fuckin' bastard." Separating me from you, he seemed to be saying, roping me off like a freak, like an enemy. He stood there with his big blond pompadour, gold-capped tooth, snazzy suit and funky shoes, uttering unselfconscious profundities and pulling at his necktie like an oversexed Rodney Dangerfield. I saw nothing but a guy on the stage; any trace of femininity was either gone or thoroughly obscured, and the politics, while up front, were strangely dislocated from the erotic reality of the performance. Instead of a woman, I saw, as Fischer says,"a funny man" with a great big bulge in his left pant leg where his absurdly erect penis was lodged. Acting as M.C. for the evening, Mr. Dick worked the mic like a stand-up comic, bantering back and forth with the audience. Fischer likens him to Andrew Dice Clay; loud and crass, he's a womanizer who claims he's"no homo." He flirted unabashedly with the women in the audience and then introduced them to his fiancée, Bob, a"female, female impersonator" ; she called him"Daddy" and ogled him adoringly. The two of them then did a duet à la Sonny and Cher, called, "I Got You, Bob," which included the following refrain sung by Bob:"And when I'm bad/at goin' down,/if I use my teeth,/you slap me around." Fischer explained,"The persona, the character that I have adopted, is in your face. In your face! He epitomizes the stereotypical attributes that I don't like in men." Still, he's good-looking and amusing, and somehow strangely sexy, too; one ends up liking him despite the fact that he's not really a likable guy. Fischer, for her part, would have it either way, and is in fact most flattered when people claim,"I hate you!" "Thank you!" she returns happily, convinced that she is doing something right. When on stage, Fischer prefers to stay completely in character as a man; it is for this reason that she generally does not strip. She does, however, do a rather a mind-boggling genderfuck number called, "Are You a Boy or a Girl?" where she appears, from the head up, as Mo B. Dick. The problem is that, from the neck down, she's a babe with gorgeous gams in a wonderbra and pumps. Halfway through the number she allows the audience to see her erect"penis" beneath the negligee. Fischer told me that she feels"more like a man in a dress" than a woman during this number."I've got the facial hair and the pompadour, and I put on a wonderbra and I've got a slip dress, dildo and fishnets, and stilettos. So I'm feeling my tits and then I feel my dick, and then I'm all {confused}, and I can't figure out, are you a boy or a girl? So it's this whole weird hermaphrodite kind of performance, and it freaks people out. Because, if I start working out really hard, going to the gym, I could be all buff. And then I've got these fairly pretty legs, so that would fuck people up even more. "I did La Cage Aux Folles,'I Am What I Am.' It's funny because it's a woman dressing as a man dressing as a woman. I come out in this long wig and kimono, and I rip it all off, rip off the wig. And underneath it I've got fishnets and stilettos, and boy's underwear and a T-shirt, so my tits are strapped down. So that's another weird bend.'I Am What I Am -- well, what are you?! I like genderfuck stuff like that more than blatantly coming out and exposing my female self. I haven't done that; I don't know that I will. Maybe I will, maybe I won't. Because to me, it takes so much work to maintain the male persona. That's a lot of work, capturing that, keeping that, maintaining that illusion. To me that's the greater part of it, really working on it. Because I'm a woman every day, all the time."

Betsey

Gallagher photo by Lucien Samaha, c. 1997 The Face "I really want to run for President." - Betsey Gallagher

I first read about Betsey Gallagher in The Village Voice in late 1997, when her alter ego, Murray Hill, was running for Mayor of New York City against Rudy Giuliani. Perpetually 45 years old, Murray is a short, fat, middle-aged white guy, a regular working schlub with a wife and two kids. A laid-off token-booth clerk, he wears conservative suits and wide ties, gold-framed glasses, and his hair slicked back and parted on the side. He greets everybody with the same,"Hi, howya doin'?" and sends them off with a hearty"God bless ya!" You almost don't notice his breasts. "Hey, a lot of middle-aged white guys have tits," says Gallagher, the 27-year old woman behind the mascara mustache,"You know. You've seen them." She conceived Murray while studying for her Master's degree at the School of Visual Arts, where her focus had been on photography. She'd come to New York from Boston University in late 1995, bright-eyed and enthusiastic, a portfolio of drag queen photos tucked under her arm."So I had this body of work," she told me,"and then I thought,'Okay, I'm going to New York, and I'm over Boston. I want to go to New York and be a photographer.' Just like everybody else. Little did I know that the work I was doing, everybody else was doing." The message finally got through to her at Wigstock."I was down there and I saw millions of photographers. Everyone was doing the same thing, literally. It was like (mimes a dropping bomb), New York, let's face it now! I was totally freaked out. The whole situation just weirded me out and I had this epiphany. All these guys were around, all these fags, so many people, so many photographers. And there were no dykes." Right then was when she stopped taking photos of drag queens. Deciding instead to document the women and lesbians she knew must be out there, she began looking for drag kings. Her timing could not have been better, for it was shortly before the birth of Club Casanova and a series of drag king contests were being held at the Her/She Bar in Chelsea."I was there as this little naive photographer, taking photos of everybody, the whole scene. In the beginning it was very mellow, people would just walk up on stage, and I'd think,'Oh, I could totally do this. I could really be funny and do funny things.' But there was still the camera; I was tied to the camera." Despite her desire to perform, she was not yet ready to move from the silent to the spoken. "So I had all these photographs and I was showing them at school. I got some work published, and everyone at school was really excited about it. But then I was like,'Fuck the art world.' It wasn't satisfying for me and I wasn't reaching my goals by putting up photos for grad students, or putting up photos for art people. Because I wanted to show lesbians, and show drag kings, and show what was going on to everybody, to get it out there. I mean, it's not really that effective to show it to this very small group. I wanted more. More, more, more, more. So there was a conflict happening with that. The photographs were great, and they were well-received, but it wasn't enough." Eventually a friend offered her a job as a cigarette girl --"with the dress and heels and pumps" -- in a new nightclub known as The 999999s, a"straight, trendy, cocktail-lounge kind of place." When he offered to buy her a dress, Gallagher tried to think of the role as"girl drag," a pure performance. Still, she could not shake her sense of discomfort. Thinking twice, she phoned her friend and told him,"I want to do this, but it's not going to work out." When he offered to buy her a suit instead, she was instantly relieved;"I think that's going to work a little better," she replied. And so she began working on Sunday nights in drag, pushing cigarettes and taking photos of the customers. Shortly thereafter, Gallagher began appearing regularly at Club Casanova, where she did a series of wickedly funny drag impersonations. Her various incarnations included a gray-haired Bela Karolyi, urging little Kerri Strug on despite her broken leg, holding out the promise of a meal as reward; she was John Travolta on Grease night and Elvis on Elvis night, albeit in his"puffy," later days. It was a busy time for Gallagher:"I was at The 999999s every Sunday and then I would go to Casanova for these little shows. It was the same night, so I'd work at The 999999s till one, take a cab over, do the show, go back to The 999999s till four o'clock in the morning. That kind of thing." She was still in school at the time, attending classes and taking photos, but her interests were steadily moving away from photography and more toward performance. The conflict grew until a supportive professor took her aside."There was just a point where she knew there was so much tension there, and it wasn't working for me to try to stay in the photographic medium. So she said,'You gotta' stop taking photos. You need to concentrate on this character. You need to do this, you need to work on this. Don't waste your time in the darkroom. You need to be doing this full-time'." So Murray was born, and the fellow who began as a sleazy sort of playboy lounge-singer snapshot-hound was transformed into Mr. Hill, the clean-cut family man. The reason for the change, of course, was political; this became clear the night Murray tossed his hat into the Mayoral race at Club Casanova. Rudy Giuliani was up for almost uncontested re-election on a platform that promised to continue closing down bars and nightclubs, mostly businesses that happened to be queer spaces or downtown performance spaces. Someone had to stop him, so Murray went out stumping:"Mayor Ghouliani is trying to clean up our city," he railed,"and I will not tolerate his behavior!!" Hill promised to give New York City back to"the young people," to"make sure that New York City is dancing every night of the week, 24 hours a day, 365 days of the year." He preached a brand of"family values" that included respect for the rights of lesbians and gays, claiming,"I'm not gay, but my daughter is," despite the fact that she was only six years old at the time. He shook hands at street fairs, night clubs, and queer events, winding up in newspapers and on television. When the race was over and defeat conceded, Murray settled for the distinction of having Gallagher write her Master's thesis about him. He scaled back his operations a bit, preferring to stick to nightclub appearances where he has built up a repertoire of over fifty songs, all"big numbers" which he puts over with a style all his own; he can't really sing, but his attitude is stellar. Most of his gigs are at straight clubs frequented primarily by white people with enough money to pay for a $25.00 glass of Scotch, or at least a few well drinks. He's fond of limousines and entourages, and is usually on his way to going somewhere else. He works often with his wife, Penelope Tuesdae, whom he met thirty-five years ago at a karaoke bar -- he would have been ten years old at the time. They have been married for twenty-five years, and she's been played by at least three people. Murray thrives on this kind of incongruity; his mustache is painted on, his breasts are obvious, and his son is sometimes played by a plastic doll. I met Murray near the beginning of my fieldwork and saw him thereafter several times; not once did I catch a glimpse of Betsey. Gallagher rarely makes a public appearance out of drag, and when she is in drag, she is completely in character. Brash and overblown, Murray insists that you respond to him as Murray, and there is nary a sign of Betsey. I was always"kid, " to him, and I could never be certain whether or not he was taking me seriously. I remember wondering where the line of demarcation was; where did Murray end and Betsey begin? I recall telling Mildred Gerestant, a.k.a. drag king Dréd, how I felt around Murray."It's kind of difficult to negotiate for me," I explained,"because from one minute to the next, I'm not sure how to respond. Am I reacting to the male character? Am I reacting to the woman inside? Because when I'm with Murray I'm totally reacting to Murray. It's like, I have to react to Murray because Murray doesn't give me a choice; there's no Betsey there to react to. And with Maureen, it's like, when she's in drag as Mo and she's on stage or she's on her way to being on stage, if she's getting in character, she's very solidly in character. But once she steps off stage and you start talking to her, little by little by little, she falls out of character. And then eventually I'm talking to Maureen in a mustache. And it's wild to feel it happen." Gallagher was the last person I interviewed for my project, almost six months to the day from the first time I met Murray. I admit it was a shock, as I had no idea what to expect when I met her at her Brooklyn apartment. As I stepped out of my car, she leaned her head outside her second-story window and whistled. I looked up and briefly caught sight of her face but did not recognize her until she met me at the door. Even then, it was a surprise. I'd had a feeling that Gallagher might be the one true butch dyke among the drag kings I'd found, but to have my thoughts confirmed was slightly unsettling. After interviewing Mo, Dred, Shane and all the others, I'd gone from expecting butchness to anticipating femininity. Not that Gallagher isn't feminine -- she is a woman, after all -- but she was the lone drag king to own up to the"butch" label."I like to think of myself as butch," she told me,"but any girl I ever dated will tell you otherwise -- damn them!" To me, she looked the part. The thing that stands out about Gallagher's act is the obvious fakery of her drag. She uses only mascara -- Cover Girl, she's quick to mention -- for her mustache; it should look, she explained,"like you're trying to have it look real, but it looks fake, so fake, like in the movies." The Groucho Marx wax-looking lip ornament comes to mind."I mean," she went on,"I definitely do it because it's also very convenient. But it's funny. I think it's funnier to have this dumb-ass mustache painted on. Some people are like,'What's that?' And other people, they don't recognize. Because it does look kind of real." Surreal, I would say."Yeah, that's kind of my deal," she admits with a wry grin,"and I have the gold pinky ring, gold watch, and the slicked-back hair with the Aquanet. Yeah, I'm a cheeseball." "And you don't bind your breasts," I stated, intending it as a question."Too big," she gestured."It's true. Forget it." I asked her if she'd ever tried."Early on, I did, and I couldn't breathe. I wear a sports bra. But one time I bound, and they were flipping up from the bottom. And I was like, this is bullshit. I don't have time for this." I suggested that there is no real moment when Murray actually tries to pass."No," she agreed,"and I think that's what makes it more real. I'm not about exposing to the crowd that I'm a woman. I never get out of character when I'm out as Murray; I always stay in character because I think that's more effective and more powerful. Because that's what people don't know. I'm not letting people know, I'm not giving them what they want. Not the gay crowd; they know. But I'm never revealing overtly that I'm a woman underneath. Obviously I am; there are my tits, there's the whole thing, everything's there. But I'm staying as this character, and that edge is more powerful, I think, than whipping out your dick or showing that you have tits. "So there's that and there's also the component that -- I always shy away from it. I don't discredit other people or performers that do this, but I just have a real problem with the sex and all the perversity. I didn't want to bring that to my act. I get kind of very subtly sleazy with the girls. I make off-the-cuff comments. But I never wanted to have it just be about the raw sexuality, because I perform for a lot of straight people, too. And I feel like they want to see that and they think drag kings, drag queens -- okay, that's what they're going to expect. So I've tried to have a more conservative act, but to use humor and comedy, and try to do original, fun stuff, and not do that kind of stuff. I want to try to have it be this character, this person, and not be a spectacle." So Gallagher, as Murray, does not"pack." ´ To her,"wearing a dildo or a strap-on doesn't make you a drag king or not a drag king." I suggested to her the possibility that there is a metaphoric relationship between a drag king's choice of"packy" and her attitude toward drag in general."Yeah," she agreed."Some of the other drag kings have made fun of Murray. It's funny, I am aware of the theories, and they do try to emasculate me all the time. Like,'Aw, Murray,' they're like (mimes grabbing a crotch),'Aw, you faggot, you have a little dick.' So yeah, those things are in play." Intriguing to me here is the level at which the other drag kings are employing the label,"faggot." As a"guy," the other"guys" taunt Murray just as biological men might, calling him out as a"faggot" for being unable to have sex with women (by virtue of his absent phallus). In similar fashion they accuse him of being too polite for masculine values. The dominant stereotype, fully internalized by the drag kings as women, occurs quite naturally to them as men -- albeit rather nasty men.

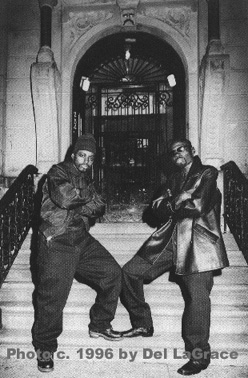

as Dréd as Dréd

photo by Yvon Bauman "Just looking at yourself in the mirror and seeing yourself actually transform is so, so beautiful. I think everybody should try it." - Mildred Gerestant

On a Thursday night in mid-April I paid my first visit to the Dragnet event at Crazy Nanny's. It was a warm and pleasant evening, and a woman stood outside checking driver's licenses and collecting the price of admission. A butch dyke in a baseball cap and cotton jacket, she smiled when I approached and asked,"Is there a drag king show here tonight?" "Yes," she replied, introducing herself to me as"Mega Boy Kate," the promoter of the event."Why? Do you want to be a drag king?" I laughed embarrassedly and explained,"Oh, no. I'm a student at Columbia, writing my Master's thesis on drag kings. I'm just here tonight to sort of introduce myself, lay a little groundwork." "Oh yeah?" she inquired, eyebrows up, and began briefing me about the drag king scene at Nanny's. Kate became a friend to me almost immediately, recommending me enthusiastically to all of the performers, keeping me as company through those first awkward weeks until I achieved a working level of comfort at the bar. I was profoundly ill at ease there in the beginning; insecure despite having a committed partner at home, I was as afraid of looking available as I was of being unattractive. It helped immeasurably to know that I was not precisely there alone -- there was always Kate to chat with. At 11:30 p.m. I found myself sitting in the still-empty club, waiting for the crowd to arrive and the show to start. With little else to do, I began taking superfluous notes. I pulled the promotional card I'd picked up at the door out of my pocket and examined it, noting the words,"$5.00 cover, $3.00 if you're in drag." I looked down at myself and wondered, why did I pay five dollars? Dressed up for a night out, I was wearing black jeans, black men's shoes, a button-down shirt and a necktie. True, I was not attempting to pass as a man; I was simply a butch woman in a necktie. Still, the question nagged at me: Why was I not in drag? I approached Kate and said,"Can I ask you a purely academic question? It's not that I'm cheap or anything, but I was wondering. The flyer says'five dollar cover, three dollars if you're in drag.' I paid five dollars. Am I not in drag?" "No. You're not," she responded flatly. "Okay," I conceded,"I'm not." After all, I was not intentionally trying to do drag, or to pass as a man; the latter was simply an unintended consequence of my self-expression. Still, I wanted a definition, or at least the beginnings of one, as a place from which to start."But I want to know," I went on,"why am I not in drag? What constitutes drag?" Kate looked me up and down and raised an eyebrow."Are you packing?" "No," I blushed, instantly grateful that I even knew what she was referring to."Not right now," I grinned. "Packing," she explained,"facial hair, a full suit --" "So it's got to be all the way?" She nodded."So when somebody says they're in drag," I joked,"waddaya do? Give'em a squeeze?" "Well," she answered seriously,"I pat'em down. The other night I had someone come in here, FTM. He said he was in drag and I said, 'No, you're not. You're not in drag. You do that all the time. That's who you are.' That's not drag." "So it's a performance, then? It has nothing to do with identity." "Right. I get butches come in here all the time, they say,'Yeah, I'm in drag.' I tell'em,'No. No, you're not. You didn't put that on, that's who you are. You wear that all the time, out on the street.' Can you change your look entirely? Can you put it on?" I nodded, understanding."Or," she continued,"you can do reverse drag. You can put on a dress, and heels, a wig and makeup, and I'd let you in for three bucks." "You mean butches, right?" "Yeah," she confirmed, eyeing me directly."If you came in here in a dress, you'd be in drag." "And I'd get in for three dollars?" "Yeah." "That's okay, I'll pay five." I left Kate to her business at the door and tried to assume an air of nonchalance, surveying the room around me. There were so many butch women there -- any one of them could be a drag king, I mused. All it would take would be a mustache. The masculinity is already there, I reasoned; all that's lacking is the masquerade. But when Mildred Gerestant arrived a short time later, I realized I was wrong; a mustache alone wouldn't do it. Masculinity is not equivalent to maleness. Scheduled to perform that evening, Gerestant had dressed at home and traveled to the club in drag. Yet despite the bald head and crisp goatee, I perceived her as a woman immediately. While it might be more appropriate here to refer to the drag king as "he" because the performer was in drag, in this case Gerestant had not yet adopted the requisite male persona; she was simply a female performer in make-up, not yet "in character." The performance of Dréd would require her to suppress her femininity, a step she had not yet taken. Even butch women do not necessarily suppress their femininity so much as they express their masculinity, but to be convincing as male requires the eradication of femininity. When femininity is markedly present in a man, it marks him as"other." While many drag kings like to play with this boundary, as women who make convincing men who are sometimes effeminate, Dréd, in full character, was never effeminate. Once he took the stage, the masculinity represented by his beard became naught but a sign for some sort of internalized maleness, confounding the old adage that"clothes make the man"; clearly, it was his attitude that did that. Dréd was the first drag king I ever met and the first I ever saw perform. As such, he shaped my initial perception of drag and the outlook with which I approached the subject. His performance confirmed for me the complexity of masculine drag as well as the wit and intelligence of those who perform it; I found myself awestruck by the power of the representation, compelled by its polyvalent eroticism. Admittedly, this is a credit to Gerestant, herself, who is truly at the top of her game as far as drag is concerned; in under three years she has developed something of an international reputation. Her act is truly mesmerizing, and my eyes glazed over as a smile spread across my face."Brilliant," I kept telling myself,"really brilliant." I was not alone in my judgement, as Dréd appeared to have little problem soliciting dollar bills from the excited women in the audience. The success of Gerestant's performances are a testament to the amount of time and energy that she puts into them, and other kings are quick to recognize that she is one of the hardest workers among them. Her act is all lip-synched, she says, just for now, until she is ready to begin singing. But while the lip-synch is nearly always dead-on accurate, it is the way Dréd moves that makes him so convincingly male. His hands and arms, aggressively outstretched, claim the space around him, pulling it closer, owning it completely. He may rely for emphasis upon stock moves and expressions found in hip-hop music videos, but the core of his masculinity runs up his spine and through his face. His body posture is heavy and thick, one foot forward, aggressively leaning; his facial expression -- eyebrows furrowed, the self-assured glare, the snarling lips; these are the qualities that buy him currency as a man. Utilizing the songs of his medley to set different moods, Dréd moves through a series of costume changes within any one performance. Entering perhaps in army fatigues as a"gangsta" rapper, a change in music allows him a moment to turn his back to the audience and strip down to his next layer, be it a polyester-clad, afro-sporting Shaft or a leather-coated, braided, beaded Rick James. Sometimes just the sight of him putting on a signature hat or wig, his back to the audience, will elicit cheers. If his act stopped there it would be entertaining enough, but more impressive is the transition he then undergoes from male to female, made all the more powerful because Gerestant is so convincing as a man. Dréd strips down, layer by layer, through various male personae to reveal at last the woman beneath them all. She pulls open her shirt to expose her bikini top and breasts -- no need to bind them -- and then unzips her pants to show a jockstrap noticeably bulging. The moment, complete with breasts, facial hair, and, "phallus" all visible is, in itself, definitively genderfuck. Reaching into his jock, he pulls out an apple and, Garden of Eden symbolism and all, takes a bite. He then turns his back to the audience once more, composes himself, and returns, despite the facial hair, as a woman. Her body language shifts, her posture and her face change, and Gerestant becomes once again a beautiful, sexy woman in make-up. I interviewed Gerestant well near the end of my fieldwork, having finally pinned her down after months of trying. Like many of the other drag kings I worked with, she keeps a 9-to-5 job in addition to performing what sometimes amounts to several nights per week. Each night I saw her at Crazy Nanny's, I asked her how she was, and every time her answer was the same:"Tired." She's making some money doing drag, she says, but not nearly enough to give up her day job. I'd seen her perform many times by the date of our discussion, but was nonetheless unsure of what to expect when I arrived. While I knew her to be a feminine woman whose gender was to me, unmistakable, I was less certain of her actual self-image. The bald head, she told me later, confuses people sometimes, and I must count myself among them. I may not have mistaken her for a man, but I did expect her to be somewhat more masculine than she actually was. Lithe and lean, she sat cross-legged on her futon and, in a voice so soft I had to strain to hear, told me about her talk show appearances. "I was on Maury Povich and recently, on Sally Jesse Raphael. Both of them did the same subject. It was a pageant with eight contestants, and the crowd had to figure out by the end of the show which were really women, and which were men in drag. We all were dressed as women; we had the wigs, the gowns, the make-up on." Spaced about two and one-half years apart, both shows ended up in pretty much the same way."At the end they started reviewing each one; they would show you baby pictures. But when they got to me, for example, on Sally Jesse Raphael, I came up and Sally said,'What are you, a man or a woman?' And I said,'Well Sally, let me show you.' The crowd was yelling'man! Man,' and I couldn't believe it, because I was all prettied up and everything -- I had a long wig on. Maybe because they knew the wig was fake, or they could tell. But they were yelling,'man! Man!' And I love tripping them up! I was just laughing inside. So I said,'Well, Sally, let me show you,' and I pulled off the wig, and I was bald. And then when they saw the bald head, they started yelling,'Woman!' So who knows?" The audience response was exceptionally ironic because it is Gerestant's bald head that, under ordinary circumstances, sometimes convinces others that she is a man. Even when she's wearing make-up,"people just see the head. And they'll say'sir' without even really looking at you. Which is really, like damn, where are you living? What time are you living in?" When she is in drag the situation only grows more complex."Some people still think I'm a man -- it's happened a lot of times -- even after they see the cleavage, a bikini bra. The hair on my face is what's confusing them. And one guy, I was at this club once and he was like,'Are you pre-op?' He thought I was a man who was in the middle of a sex change. You know, like maybe I just still had the breasts, or maybe I just got some breasts and I just didn't, you know,'ka-ching' or whatever." As a butch (or relatively masculine) lesbian, these statements confound me; to me, Gerestant is so obviously female. If she is passing as a man when she is not in character, then surely she must be a fairly effeminate one. "My being bald now," she explains, by the way,"has nothing to do with the drag, just for the record. I shaved my head because I got tired of perming it and putting in extensions and gelling it up and all that." Fed up with the time it took to maintain it, she says,"I cut it short and then I shaved it a month later, after some encouragement." Being on the street, she says, can be difficult,"because, you know men -- the ones that are old fashioned or whatever -- can't deal with it and have to say some stupid comment. But then there are also a lot of compliments, like,'Oh, you have a beautiful head,' and,'It's a beautiful shape,' or,'It brings out your features.' My mother is still not quite used to it after three or four years, now. But it's okay. It's my mom, what do you expect?" She smiles, shrugging."But she still loves me, and she wants to come see my show." "The first time I got interested in doing drag," Gerestant related,"was probably when I first started seeing drag kings at a party in the East Village called, 'The Ball,' at the Pyramid Club. Some of the first drag kings I saw were Buster Hymen and Justin Case. I was just, probably attracted by the women disguised as men. And also, I thought it was very empowering. I was like, wow! I'd like to come up and do that, and be a stud just like them, in drag. It took me a while. I kept running into Buster, and I kept telling her how I wanted to try drag. We made plans and she came over to my place one day and we put on the mustache, which was really cool. She showed me how to apply the facial hair and stuff, and then I experimented with it, how I wanted it. "She was doing shows monthly called, 'The Drag King Dating Game,' and somebody had dropped out, so she asked me if I would replace her. It was my first appearance as Dréd, and this was December 1995." It was there that Dréd discovered his"superfly, mack-daddy" look, modeled on the music -- like the theme from"Shaft" -- that Gerestant had loved as a child."Afterwards," she recalled,"I got a lot of positive feedback, and it felt really good. I think that's when I also met Mo B. Dick but she wasn't in drag -- Maureen. She had this contest coming up, a drag king contest, and she encouraged me to enter it." Gerestant, however, was still too frightened to commit to the appearance; it was Fischer who pushed her to do it. Dréd won that competition and thereafter began his longtime association with Club Casanova. Gerestant credits the other kings with bringing her into drag and making her feel welcome there."Mo B. Dick helped me," she said,"she pushed me to really do drag. And Buster Hymen helped me. It's always good when people, your peers, are helping you get started. And there was real companionship there, and we did a lot of shows together."

photo by Yvon Bauman "I'm a woman with facial hair, imitating a man, and I can't get you pregnant. And I have breasts! You've got everything! What more could you ask for?" - Shane